A ‘whole host’ of meanings

Raimund Stecker explores the myriad associations of Imi Knoebel’s ‘Centren’ series – from old German, to music – and comments on a new series on display at von Bartha in Basel

Raimund Stecker is an independent publicist and author for various art magazines as well as a professor for art history at the ‘Hochschule der bildenden Künste’ in Essen, Germany.

26.11.2020

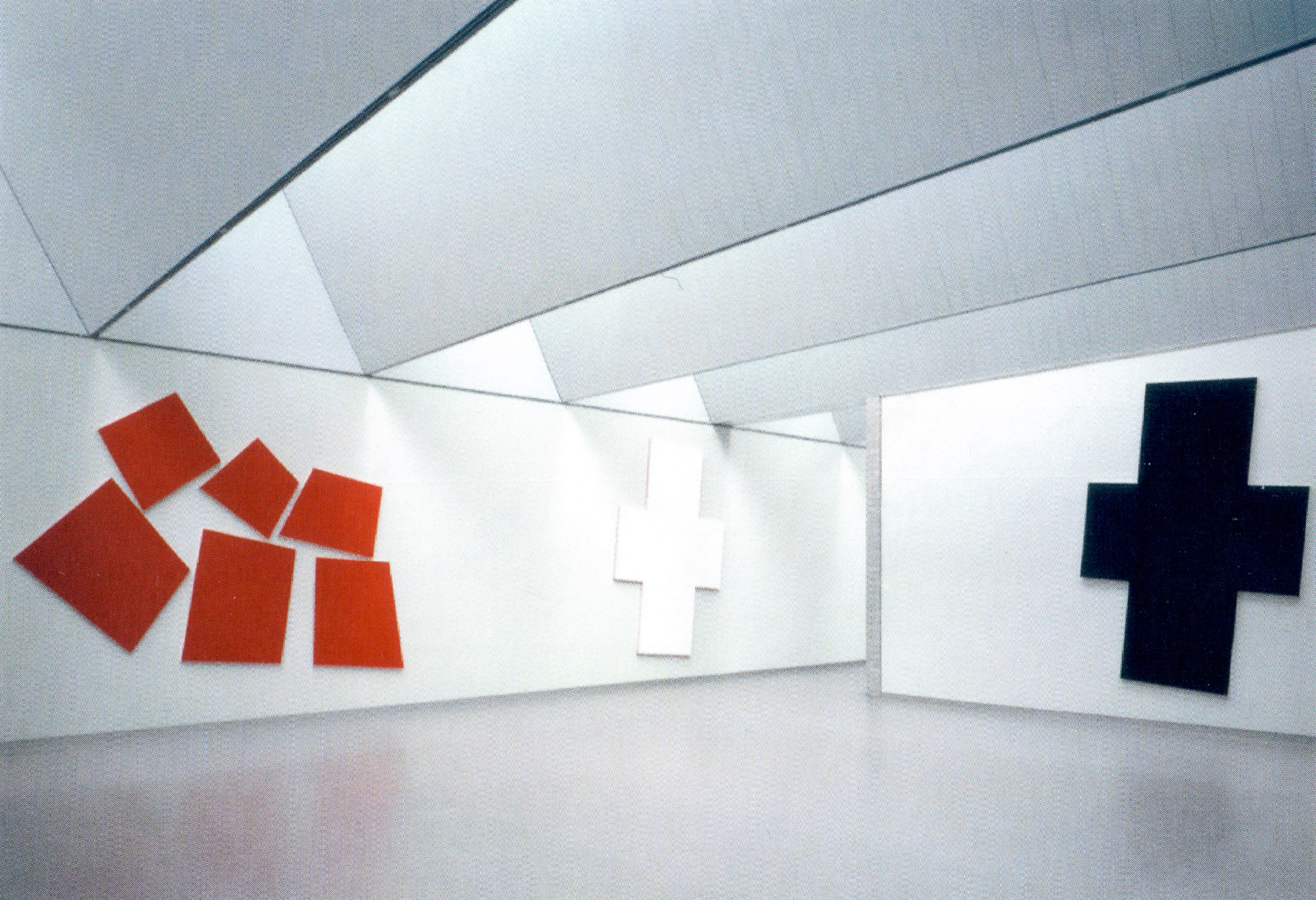

Exhibition view

von Bartha, Basel, 2020

Exhibition view

von Bartha, Basel, 2020

- It is only by engaging with Imi Knoebel’s pictures that they become more familiar. Then, however, they unleash a whole host of associations that are, of course, different for everyone: thoughts about resistances to be broken down; freedoms to be experienced; confusion from which order arises—or even the need to experience a subtle kind of beauty.

“R.” in the WAZ, thirty-nine years to the day after the end of World War II and a “good” year and a half before the death of Joseph Beuys

Centren (Centers) for Basel

Das Geriede means “the cleared thicket,” a place cleared of all bushes. According to the Brothers Grimm’s Deutsches Wörterbuch (German Dictionary), first published in 1854, it is a “variant form of ‘Gereut”, meaning something that is uprooted, which can still be found today in place names containing “Ried”, the German term “Reetdach”, meaning a thatched roof, and in the English word “reed.” In the Frühneuhochdeutsches Wörterbuch (Early New High German Dictionary) it is also defined as “edible beef entrails”, “frog and toadspawn”, and “structure, context”, as well as being related to the words “Geschlinge” and the rather wonderful “Ingetüm”, both meaning the entrails of a slaughtered animal. The word for tallow, “Unschlitt”, also sounds somehow phonetically related. And similarly, when searching for the definition of the obsolete “Geriede”, you might come across the old saying “weder geschik noch gerik haben”—loosely corresponding to the English idiom “to not hold water”—which admittedly does not sound entirely logical, but it does sound fascinatingly emotive. Googling the phrase will lead you directly to Imi Knoebel, for Das Geriede was the title of the catalogue for his Otterlo image series, produced 40 years after the end of World War II in 1985.

Otterlo VI, 1985/2009

Sperrholz / Holz

(Photo: Ivo Faber)

Otterlo IV, 1985

Sperrholz/ Holz

330 x 400 x 4,3 cm

(Photo: Ivo Faber)

This series of images contained white and wood-grained pictures—their top edges jagged in the rhythm of the image panels, their sides and lower edges straight and rectangular. They were first exhibited in Aldo van Eyck’s extension of the Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller (see below) built by Henry van de Velde in Otterlo, Gelderland. They are the major prior reference points for the Centren (Centers) examined here, dated 2012–2020. The Otterlo works were hung on white walls, parallel to the shed, in a mixture of direct and indirect light and of sunlight and artificial light.

(left: Otterlo III / right: Otterlo I)

(Photo: Nic Tenwiggenhorn)

Kadmiumrot (Cadmium Red) and Weißes Kreuz (White Cross) by Knoebel were hung at either side of them, at right angles to the shed. They were flooded by sunlight and spotlights. The sunlight dominated the space, an even “lighter light” than the other lights—it became the light-forming protagonist. It cast sharp light forms on the walls, both on the space between the images and the images themselves. It made what was bright brighter still, resulting in geometric “lights” (overexposed forms created by the light, analogous to brightened shadows), “nude-like”, immaterial yet factual phenomena that entered into a dialogue with Imi Knoebel’s images. It was a site-specific hanging, in situ. The wall as image carrier became an integrated projection surface for a light-shadow performance, the whole thing a “Victory over the Sun,” as it were, to borrow the title of Kasimir Malevich’s 1913 opera—and ultimately the starting scene for the Centren (Centers) negotiated here.

If one is familiar with Imi Knoebel’s early projections, then the even earlier synesthetic light shows by the composer Alexander Scriabin will also emerge as a reference point. All that is aesthetic, perceivable and perceptible requires the constructive competition between light and shadow and backgrounds and surfaces and images and colors. This is materialized with an almost absorbing presence in the Centrum pictures in their iron oxide red. Just as light confers a shadow upon an opposing something, an “object”, giving it different shades in the sense of Edmund Husserl, it also generates light, overlighting, overexposure, and the removal of shadows. These now materialized and visible works for Basel, titled Centrum 1–5 and the cross-like Centrum, are built on what can be seen in the Otterlo image series at the museum in Otterlo.

The Centrum works in Basel mean nothing; they simply exist! Their colorfulness is not their content, but an abstract assertion. Their forms are shades. They are phenomena placed into the world. There they are now: not very geometrically tangible, technically perfected to the point of anonymity, clear, ostensibly simple, expansively powerful in the white space, uncolored color, iron oxide red, demanding to be looked at, present. Only their aspiration is boundless, like the entirety of Imi Knoebel’s oeuvre: beauty, to “experience subtle beauty”!

- Taken from—and adapted by the author through insertions—the previously unpublished essay “Die Überwindung des Schwarzen Quadrates” (Overcoming the Black Square) by Raimund Stecker.

Raimund Stecker is an independent publicist and author for various art magazines as well as a professor for art history at the ‘Hochschule der bildenden Künste’ in Essen, Germany.

Centrum 2, 2012 / 2020

Acrylic / wood

227.5 x 305 x 9 cm