The Connecting Threads in the Work of Josef Albers and Aurélie Nemours

by

Andrew Bick & von Bartha

It all started when we at von Bartha juxtaposed works by Josef Albers and Aurélie Nemours whose compositions were so similar that we wondered what lies behind. If you take just a fleeting glance at art history,

it seems as though this question can be answered easily. Cynics would claim that one just copied from the other. But beware of jumping to conclusions; there is so much more to it than that. To find the connecting threads, we invited artist and professor Andrew Bick for an unconventional study, and to curate the fourth edition of our “Exploring the Archive” series, titled “Interacting Colors.” In the following article, Bick shares his findings, summarized in four chapters: Contradictory; Double Sided; Poetic; and Intuitive.

When I was offered the chance to do this research about Josef Albers and Aurélie Nemours I was intrigued by what connections I might find between artists who exchanged no dialogue and superficially at least, had few points of common interest beyond the basics of colour and geometry.

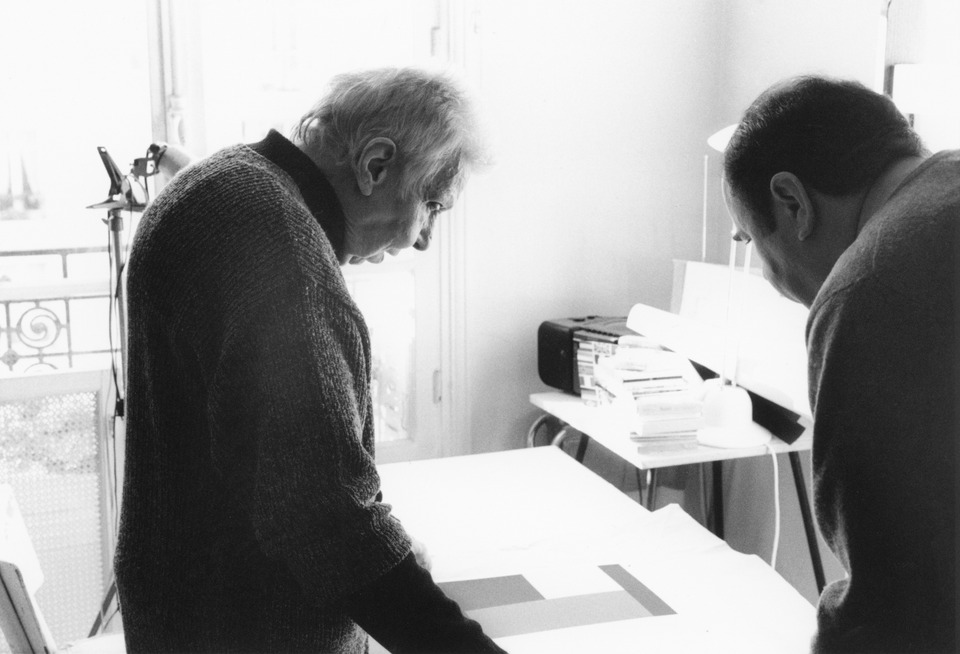

My work started with conversations with the von Bartha family about Nemours and an inspection of the archival records they kept over the decades, which are today an important source of information about the stories of many artists.

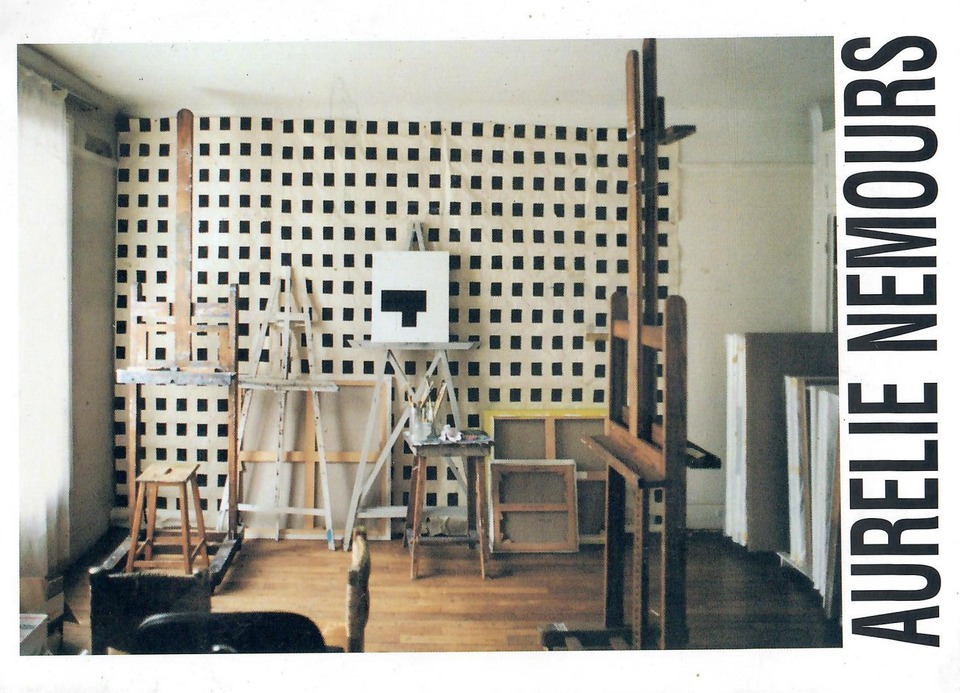

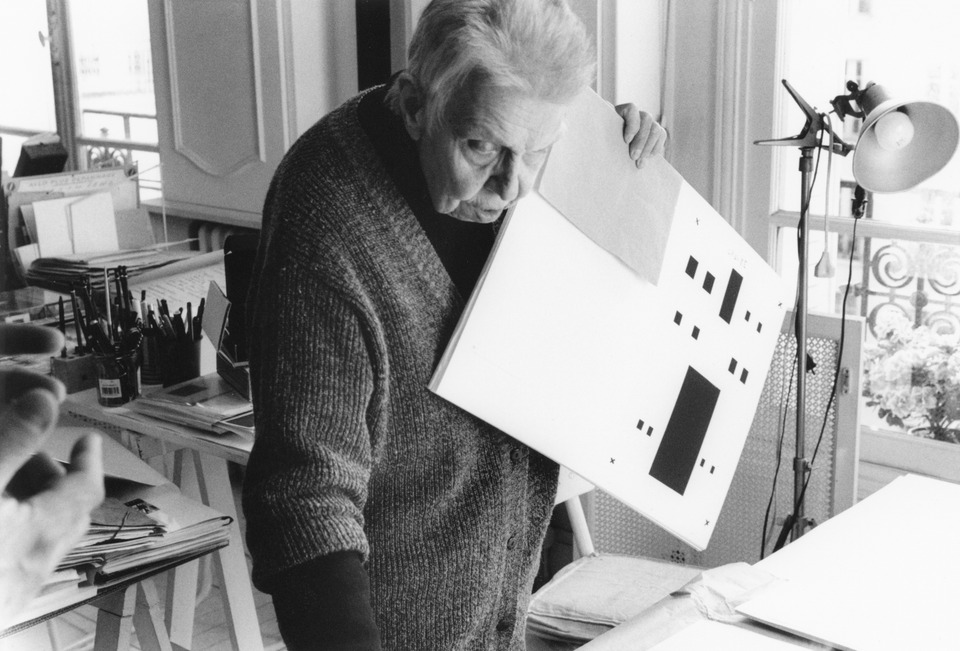

Gallery von Bartha worked with Nemours continuously from the mid-1980s until her death in 2005. Miklos and Margareta von Bartha regularly visited Nemours's studio in Paris, and the gallery consistently promotes her work. Nemours generously entrusted some of her most significant pieces to the gallery and appreciated the commitment and consequential placement of her work in serious collections. Miklos von Bartha recalls the press dialogue around Nemours 2004 retrospective in Paris:

When discussing her career at her 2004 Pompidou retrospective, Nemours responded that she had only one regret, namely that she had allowed Miklos von Bartha and Heinz Teufel into her studio. The journalist asked in astonishment why that was, whether they had stolen something? No, said Nemours (with a wink) but they always choose the best works.

This is indicative of deep commitment to the work itself but also a level of reticence on the part of the artist, which underpins the seriousness of her project. In parallel, Albers was only considered as primarily an artist not an educator after retiring from teaching.

The personal dialogue Miklos and Margareta von Bartha had with Nemours also required some counterbalancing research on Albers, a notoriously private individual whose work seems to defy anecdotal or personalised interpretation. For this I turned to Charles Darwent’s thorough and thoughtful biography [1], which deliberately sets out to examine the person more than the art, arguing that widespread interpretation of Albers’ work is not matched by a detailed understanding of the individual who made it.

Albers was variously an oxymoron: an old man making new art that was old-fashioned or, possibly, worryingly modern; an artist whose work was European in its moderation and scale, but made in America; a contemporary and a forerunner at once. Taste and the art market are conservative things, placing a premium on clarity. Albers, in historical terms, was unclear. Even more so were his Homages to the Square. [2]

Useful comparisons to the equally private Nemours were thus not only possible but became the connecting thread for the whole display. In fact, the parallels and commonalities are intriguing. They can be summarised as a shared interest in poetry which falls loosely into the category of concrete, a profound understanding of the subjectivity of colour, and a rootedness in Catholic spirituality.

I have used four key terminologies as a way of defining these parallels between the artists, and these are evidenced by the works on display themselves rather than an exhaustive cross analysis of texts on both Albers and Nemours, of which there is plenty to consider in the wide-ranging publications on both artists. These terminologies are as follows:

Contradictory,

as a conceptual root, could be applied to both artists. For both, a return to high Modernism was combined with ideas of ambiguity and allusions to the Catholic faith. Cruciform compositions, stained glass as a medium and repetition that alludes to liturgy more than system are common characteristics appearing at various stages in their work. The idea that something can look backward to the founding principles of modernism whilst at the same time looking forward to a world beyond the modern is immediately apparent in both artists’ work. At the same time embracing the traditions of one of the major religions can be easily evidenced in Nemours’ reclusive approach, less obviously so with Albers. Darwent’s biography carefully traces the Catholic roots and completed/unachieved church and monastic commissions in Albers’ oeuvre as well as his regular attendance at mass later in life. This is a world where contradiction could be an accepted part of the makeup of an artwork, and it is therefore after modernism in tendency.

Double Sided,

as a rigorous and poetic methodology, applies to Albers Hommage to the Square painted on Masonite, where, as Darwent points out [3] the backs of the paintings, with their inscriptions of colour hue, brand of colour, configuration etc, take on a poetic connotation the artist valued almost as much as the facing side of the paintings. Nemours’ dual consideration of herself as a poet/author and artist was an essential and relatively underknown element of her oeuvre, but one which resulted in the publication of a number of small volumes of poetry with French publishing houses.

Poetic,

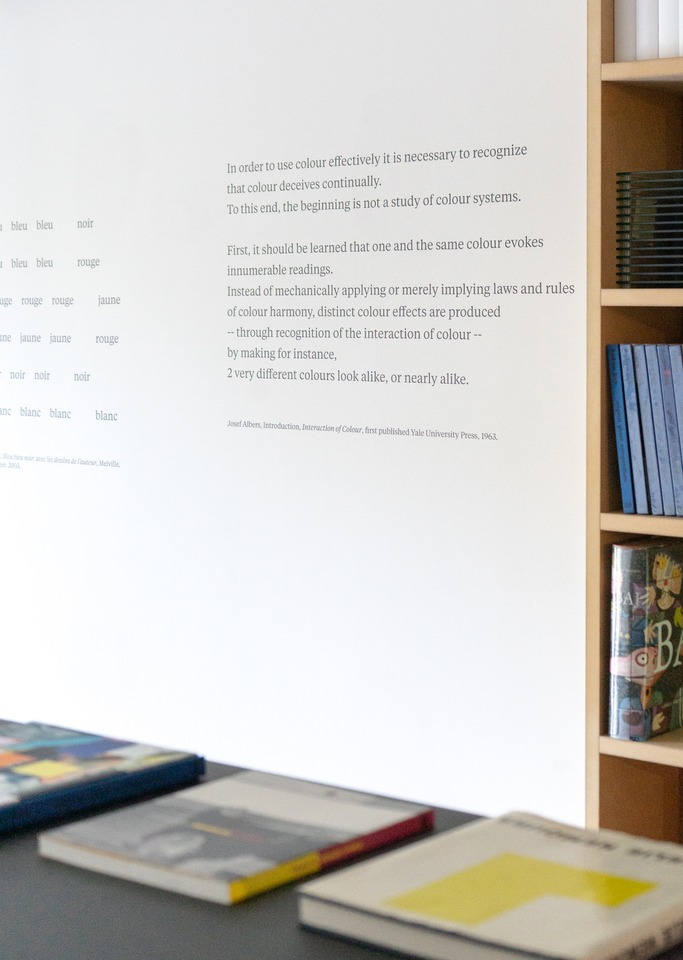

as in finding ways to make work that appears minimal but alludes to all the ambiguity of poetry and of colour. Poetics here are a means of stretching language to its extreme with the fewest possible words, while at the same time creating a form of resonance that is more than a sum of its parts. The same poetic approach to colour applies in both artists’ work and their statements as much as output indicates in each a sharp understanding of the ambiguous nature of colour perception. [4]

Intuitive,

as Albers writing in Interaction of Colour, makes clear that the intuitive and interactive both deceives and produces, …Innumerable readings. Both artists were more rooted in Mondrian’s evolutionary and intuitive approach than in pure conceptualism and system as it evolved in their lifetimes. This is distinct from the more purist approach to concrete art of Nemours’ Zurich contemporaries Max Bill, Camille Graeser, Richard Paul Lohse, and Verena Loewensberg. [5]

Nemours, interviewed for French Radio in the 1980s when she finally achieved some recognition, stated:

You study in front of nature, and you see nothing, you start seeing when nature disappears and when the shape, the rhythm, with all its secrets, comes up to the surface, rises from nature… [6]

Included in the exhibition is a full set of Albers second screenprint edition published with Norman Ives and Sewell Sillman SOFT EDGE - HARD EDGE. This portfolio of ten screenprints from 1965, followed the success of their first printed HOMAGE TO THE SQUARE series in 1962. Here the colour combinations emphasise the intuitive aspect of Alber’s approach to colour. Logically, the edges in all of the prints are the same ‘hard’ division, but colour combinations create the impression of either rigid or porous boundaries. In addition, paintings and historical publications are included, photographs from the gallery archive and correspondence. One of the original 1963 editions of Albers’ Interaction of Colour, loaned from the archive of University of Gloucestershire has been added and I am grateful, as ever, for their support of my research and willingness to lend the exhibition a valuable object.

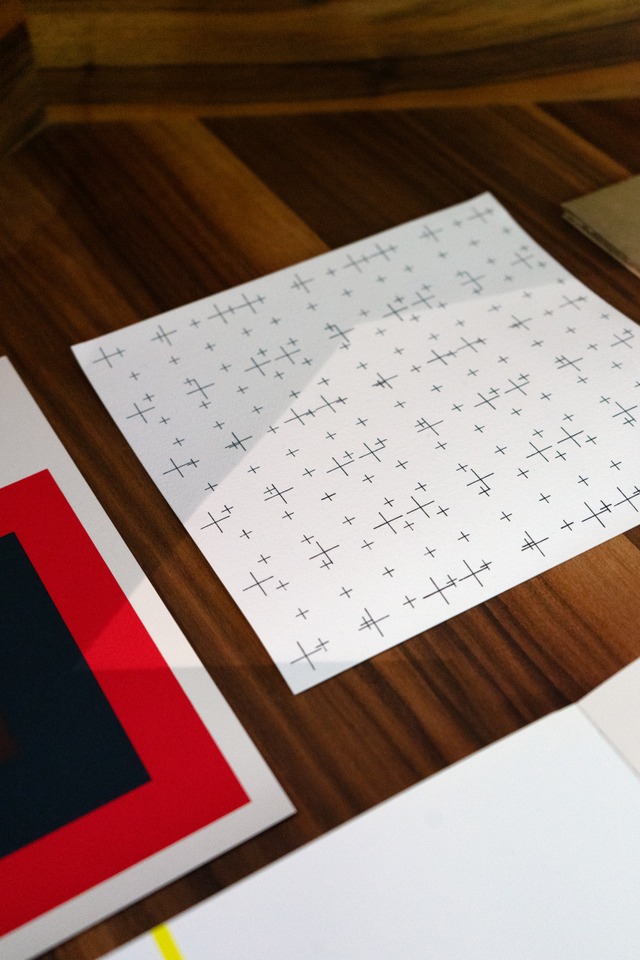

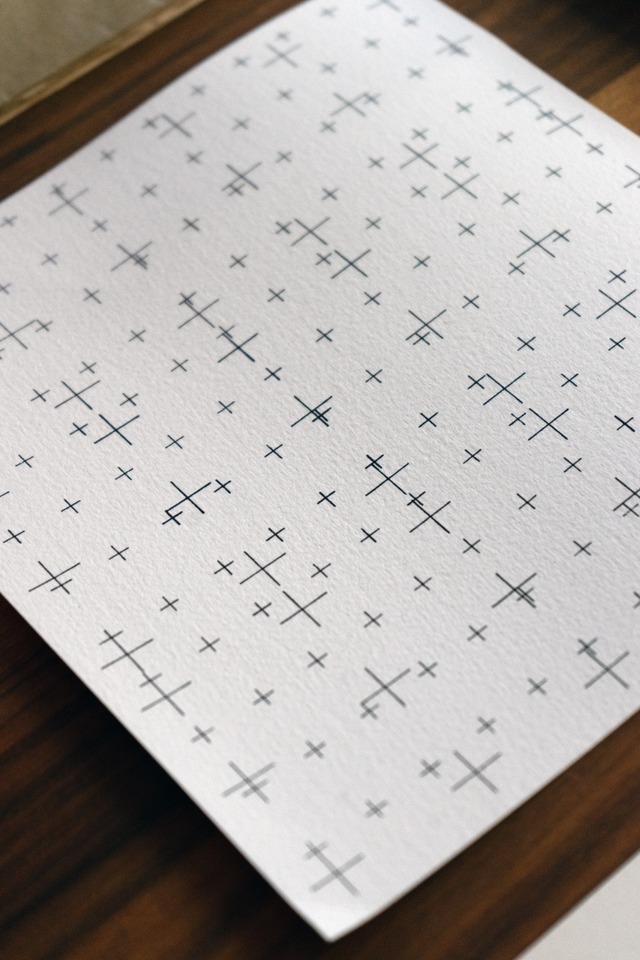

As an addition to the display, we have added a number of my works that respond in some way to what this archive exhibition considers. I note that the generic Albers title Variant is something deliberately quoted as part of my titling system since 2005. The contemplative, poetic and geometric, exemplified in Nemours approach to concrete art are fundamentals of my own approach.

This could be termed embedded research [7], where following my own artistic concerns leads me to bodies of work and legacies for which reconsideration is tempered by emotional engagement, including the highly subjective consideration of a contemporary artist. For me this includes my work on artists such as Anthony Hill, Marlow Moss, Jeffrey Steele and Gillian Wise. The poem of Nemours cited also has strong resonance with my own longstanding interest in concrete poetry and correspondence, in his lifetime with the American concrete poet Robert Lax (1915-2000).

Darwent’s extensive research on Albers, including his late and sometimes unfulfilled commissions for Benedictine monastic communities in the US, connects to my own upbringing living alongside the monastic community in Gloucestershire, UK. Although I never met either Albers or Nemours, in this sense, as a curatorial exercise, I consider the connections to be personal.

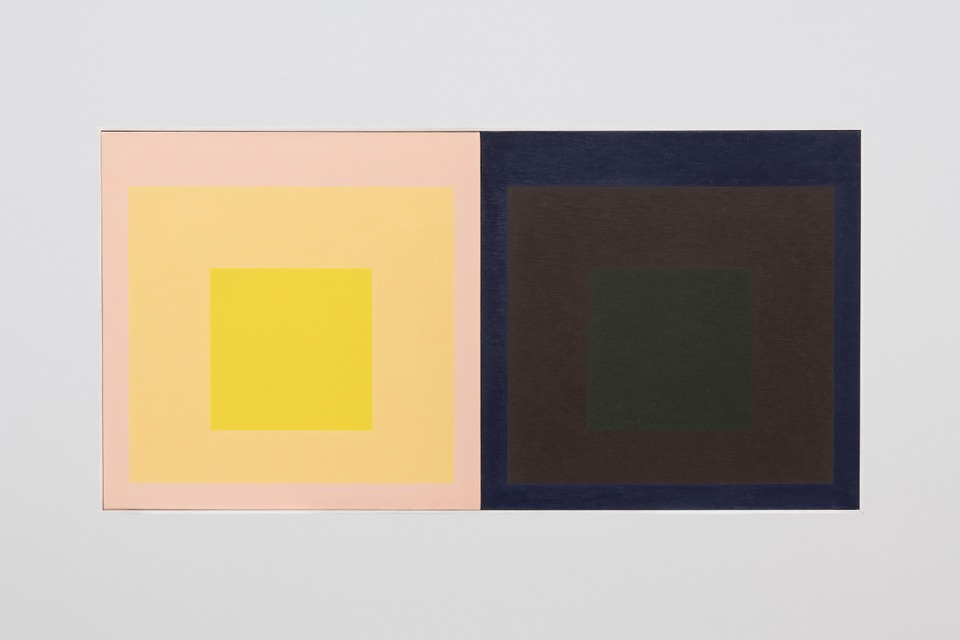

So in the end, the thread that connects three artists without personal contact or exchange with each other, is about the ambiguity within concrete art itself, where two works can look almost alike because of the commonality of the square as a motif, but the motive behind them is not the same. The short answer to why Nemours Sokaris Le Caché (diptyque droite) / Sokaris L'Acclamant (diptyque gauche), 1971 might look like Albers Hommage to the Square series is that both will have looked intently at Malevich but not necessarily at each other. Hanging work by both artists together allows their differences to resonate.

[1] https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/josef-albers-life-and-work.

[2] Darwent, Charles: https://www.port-magazine.com/art-photography/josef-albers-life-and-work/, January 2019, accessed July 2025.

[3] Darwent, Charles: Josef Albers, Life and Work, pp 25-27.

[4] Albers, Josef: Poems and Drawings, 3rd ed. (New Haven, Conn.: Readymade Press, 1958; New York, and Aurelie Nemours Midi la lune, SEGHERS, Paris, 2002.

[5] https://www.hauskonstruktiv.ch/en/exhibitions/aurelie-nemours?tab=1.

[6] AWARE: Archives of Women Artists: https://awarewomenartists.com/en/podcasts/aurelie-nemours/. (Translation to English from the original French radio broadcast of 1986, which was her first appearance on radio at the age of 76 on France Culture, Les chemins de la connaissance).

[7] Richardson, Craig,: Artists’ embedded reinterpretation. (In museums and sites of heritage Journal of Visual Culture, Taylor and Francis Online, 13 Jul 2017 for a detailed analysis of this methodology).