928 words about Francisco Sierra

Sex, subversion, style and humour. Max Küng recalls the first time he saw a Francisco Sierra painting in the flesh—and the intense longing the encounter sparked

When I go to an art collector’s house, I’m not always envious of the works on their walls. Often my feelings are quite the opposite. But every now and then there is something there that triggers within me some degree of longing, a desire to possess it, a feeling not unlike falling in love—and which makes me murmur: “Please pack this up to go, right away, now, thank you!” That’s how I felt when I once visited a collector who had an Arcimboldo hanging in her living room. A magnetic painting! But I knew, as a man of reason, that an Arcimboldo—as small as it may be, as well as it would have fit in my bag—would be too much for me to handle. But I often think back to that moment of looking at that work. It had changed my world forever, even if only by the slightest fraction; art can do that, if it is good and true.

Then I went to see an art book publisher whose apartment did not feature an Arcimboldo, but instead much of what you might call “good merchandise.” There was a single, salon-style hang on the walls, and in the middle of this was a painting he had recently acquired, 40 by 34 centimetres, oil on wooden panel. The painting attracted me to such an extent that I was inevitably reminded of the Arcimboldo moment, because it was exerting a similar gravitational force. “What is that?” I asked the art book publisher. He didn’t answer, but came and stood beside me, looking at the work for a while, as I did, and then, smiling contentedly and not without pride, while still looking at the picture, said: “Great, isn’t it?” And it was indeed.

The picture was of a bedecked fir tree, but this tree was unlike any other: the branches were male genitalia, penises, with testicles hung like fir cones from the sturdy branches. The tree’s decoration was sparse but diverse: a shiny blue bauble, a pocket watch, a burning sparkler. It was the first painting by Francisco Sierra that I had seen in the flesh. And what I didn’t know at that moment was that the seeds of desire to possess a Sierra of my own had been planted in me. From that point on this desire continued to sprout silently.

At the time the art book publisher had said that there was something about Francisco Sierra’s work that he liked in particular, in addition to the elegant and completely unostentatious technical mastery: the humor inherent in the picture. “It is very rare that good painting makes you smile, that it has humor—and good humor at that.”

He had quoted Malcolm McLaren, whose definition of punk was “Sex, subversion and style.” This is also true of Francisco Sierra’s work, which features all of these ingredients, plus one more: humour, which is to be found in everything—sometimes in good and even poetic doses, sometimes only as a homeopathic trace. Permeating the work, it allows the viewer to sense the artist as a person in every painting, transporting his spirit, his essence.

Years later I fulfilled my wish—or rather my longing—to own a painting by Francisco Sierra, which by then had swelled to a rather handsome size. I gave it to myself as a fiftieth birthday present (I almost bought a big fat watch instead … but luckily I thought twice about it). I would have loved to buy the painting he was working on when I was able to visit him in his studio enthroned above Lake Murten: a 154 by 235 centimetre photorealistic painting of three jumbo jets under construction. Francisco Sierra worked on this painting for nine months, from early in the morning until deep into the night, day after day. This testifies to the artist’s patience, his perseverance—and his faith in the subject. But I opted for a different work, because the painting of the three jumbo jets would have been too big for the trunk of my station wagon (the work was recently wisely purchased by the Kunsthaus Aarau, so there is a real chance that I will be able to look at it again soon).

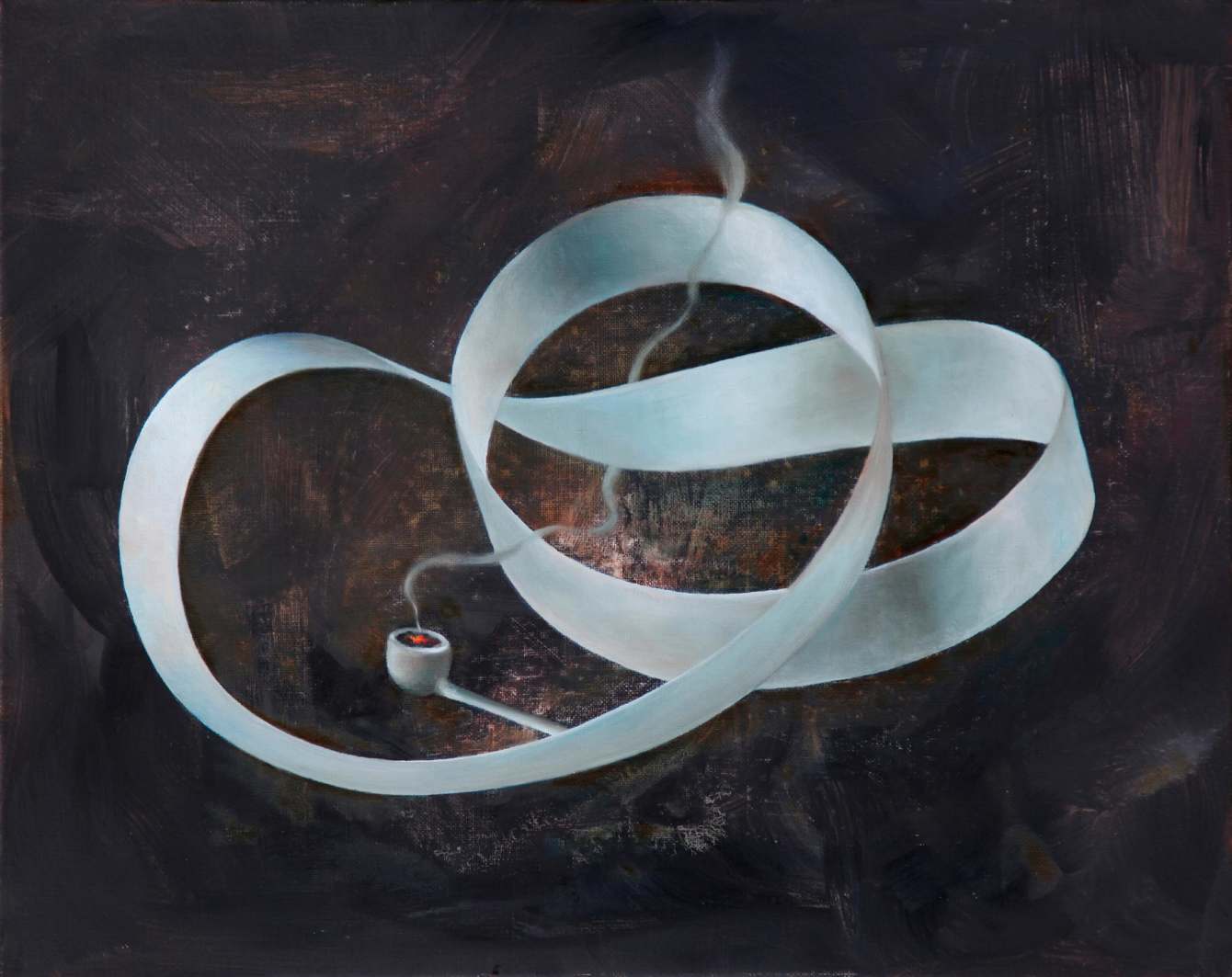

The picture of my choice measures 40 by 50 centimeters, and depicts a Möbius strip and a smoldering pipe, with smoke swirling delicately from its end and meandering through the curved bands of the Möbius strip. The picture says: the embers are still hot and everything will go on forever, because things have always been and will always continue to be. I thought the work, titled Smoking Moebius, seemed quite fitting for a fiftieth birthday, for reaching the approximate halfway point of a so-called life span.

There is this one scene in a documentary film about John Baldessari when a collector told him that he was always being asked the same question over and over again, namely which picture would he save if there was a fire in the house. It would be his painting, the collector told Baldessari, who then smiled and said: “Oh, that’s very kind of you.” Well, I would reach for the Sierra. Sure thing. Because I love this painting. It hangs in my hallway. I look at it every day; I did so just this morning before I left the house. It smiled at me. And I smiled back.

P.S. The artist does indeed have a sense of humor. I was able to confirm this for myself. He is also a very good cook, a trained violinist (so the virtue of perseverance won’t be completely foreign to him, he has mastered every vibrato variation as well as the solo ballad by Eugène Ysaÿe)—and you can have a really good, long, and in-depth conversation with him about cars. What more can you ask of a great artist?

Max Küng (*1969) was born in Maisprach (BL), where he grew up on a farm. He has been writing texts and columns for ‘Das Magazin’ for twenty years. Various books and novels, most recently the column collection “Die Rettung der Dinge” was published by Kein & Aber. He is currently working on his new novel, which will be published in spring 2021. Max Küng lives in Zurich. He is married and the father of two sons. He likes to bike.

- Works by Francisco Sierra will also be exhibited in ‘S-chanf 4+2’, starting June 30 until July 25 in S-chanf, located in the Engadin/Swiss mountains.

“Smoking Moebius”, 2016

Oil on canvas, 40 × 50 cm

Owned by Max Küng

928 Wörter über Francisco Sierra

Wenn ich bei einem Kunstsammler oder einer Kunstsammlerin zu Gast bin, ist es ja nicht immer so, dass ich sie oder ihn um die Werke an den Wänden beneide. Oft sind meine Gefühle gar gegenteiliger Natur. Doch dann und wann hängt, steht oder liegt da doch etwas, das ein mehr oder minder ausgeprägtes Verlagen nach Besitz in mir auslöst, ein Begehren, ein Gefühl, welches dem sich Verlieben nicht unähnlich ist – und das mich murmeln lässt: „Bitte zum Mitnehmen einpacken, sofort, jetzt, danke!“ So ging es mir etwa, als ich einst bei einer Sammlerin zu Besuch war, in deren Wohnzimmer ein Arcimboldo hängt. Ein Magnet von einem Bild! Doch wusste ich als Vernunftsmensch: Ein Arcimboldo – so klein er auch sein mag, so gut er auch in meine Tasche gepasst hätte – wäre für mich eine Kragenweite zu gross. Immer wieder aber denke ich an jenen Moment zurück: Das Erblicken dieses Bildes. Es hatte meine Welt – wenn auch bloss um ein My – für immer verändert; denn das kann die Kunst, wenn sie gut ist und wahrhaftig.

Dann war ich bei einem Kunstbuchverleger zu Gast, dessen Wohnung keinen Arcimboldo bereithält, aber viel von dem, was man als „gute Ware“ bezeichnen könnte, die Wände eine einzige Petersburger Hängung, und mitten drin ein Gemälde, welches er sich unlängst angeschafft hatte, 40 mal 34 Zentimeter gross, Öl auf Holzplatte. Das Bild zog mich derart an, dass ich unweigerlich an den Arcimboldo-Moment erinnert wurde, denn es übte eine ähnliche Gravitationskraft aus. „Was ist denn das?“, fragte ich den Kunstbuchverleger. Er antwortete nicht, sondern trat an meine Seite, betrachtete das Bild eine Weile, so wie ich es tat, und meinte dann zufrieden lächelnd und nicht ohne Stolz, noch immer das Bild anblickend: „Grossartig, oder?“ Und das war es in der Tat.

Das Bild zeigte einen geschmückten Tannenbaum, doch der Baum war kein Baum wie jeder andere: Die Äste waren männliche Gehänge, Penisse, wie Tannenzapfen hingen Hoden am strammen Geäst; der Schmuck des Baumes war karg, aber divers: eine glänzende blaue Kugel, eine Taschenuhr, eine brennende Wunderkerze. Es war das erste Gemälde von Francisco Sierra, welches ich in natura zu Gesicht bekam. Und was ich nicht wusste in jenem Moment: Es wurde in mir der Wunsch gepflanzt, ebenfalls einen Sierra besitzen zu wollen. Still keimte fortan dieses Begehren.

Der Kunstbuchverleger hatte damals gesagt, dass ihm insbesondere etwas an der Arbeit von Francisco Sierra gefalle, nebst der eleganten und ganz und gar unprahlerisch daherkommenden technischen Meisterschaft: Der Humor, der dem Bild innewohnt. „Es ist sehr selten, dass gute Malerei einen lächeln lässt, dass sie Humor besitzt – und zudem auch noch guten Humor.“

Er hatte Malcolm McLaren zitiert, dessen Definition, was Punk ausmache: „Sex, subversion and style.“ Das treffe auch auf die Arbeit von Francisco Sierra zu, diese Ingredienzien seien alle vorhanden; plus eben noch die eine Komponente: Humor, der – manchmal wohldosiert und poetisch gar, manchmal auch nur als Spurenelement, homöopathisch – in allem zu finden sei, das Werk durchdringe und so für den Betrachter den Künstler als Person in einer jeden Arbeit spüren lasse, quasi seinen Geist, sein Wesen transportiere.

Jahre später erfüllte ich mir meinen in der Zwischenzeit zu einer hübschen Grösse angewachsenen Wunsch, ja Sehnsucht nach einem Gemälde von Francisco Sierra. Ich schenkte es mir selbst zu meinem fünfzigsten Geburtstag (fast hätte ich mir stattdessen eine fette Uhr gekauft … zum Glück besann ich mich noch). Sehr gerne hätte ich das Bild erstanden, an welchem er arbeitete, als ich ihn in seinem über dem Murtensee thronenden Atelier besuchen konnte: Ein 154 mal 235 Zentimeter messendes fotorealistisches Gemälde von drei sich im Bau befindenden Jumbo-Jets. Neun Monate arbeitete Francisco Sierra an dem Werk. Von morgens früh bis tief in die Nacht hinein, Tag für Tag. Das zeugt von der Geduld des Künstlers, von seiner Beharrlichkeit – und von seinem Glauben an das Sujet. Doch ich entschied mich für eine andere Arbeit, denn das Bild der drei Jumbos wäre zu gross gewesen für den Laderaum meines Kombis (klugerweise wurde es unlängst vom Kunsthaus Aarau angekauft, so besteht die reelle Chance, es bald wieder einmal betrachten zu dürfen). Das Bild meiner Wahl misst 40 mal 50 Zentimeter, zeigt eine Möbiusschleife und eine glimmende Pfeife, aus deren Kopf fein der Rauch zwirbelt und sich durch die geschwungenen Bänder der Möbiusschleife schlängelt. Das Bild sagt: Die Glut ist noch heiss – und alles wird immer weitergehen, denn die Dinge waren schon immer und werden auch fortan bestehen. Das „Smoking Moebius“ betitelte Werk schien mir inhaltlich ziemlich gut zu einem fünfzigsten Geburtstag zu passen, also dem Erreichen circa der Hälfte einer sogenannten Lebensspanne.

Es gibt diese eine Szene in einem Dokumentarfilm über John Baldessari, als ihm ein Sammler erzählte, dass ihm immer wieder die eine Frage gestellt werde, nämlich: Welches Bild er retten würde, falls es im Haus ein Feuer gäbe. Es wäre sein Bild, sagte der Sammler zu Baldessari (der daraufhin lächelte und meinte: „Oh, that’s very kind of you“). Nun, ich würde zum Sierra greifen. Klare Sache. Denn ich liebe das Bild. Es hängt bei mir im Flur. Ich betrachte das Gemälde jeden Tag; so auch heute Morgen, bevor ich aus dem Haus ging. Es lächelte mich an. Und ich lächelte zurück.

Max Küng

PS: Der Künstler hat in der Tat Humor. Ich konnte mich persönlich davon überzeugen. Ausserdem kocht er sehr gut, ist ausgebildeter Violinist (daher wird ihm die Tugend der Beharrlichkeit nicht ganz unbekannt sein, er beherrscht alle Vibrato-Varianten sowie die Solo-Ballade von Eugène Ysaÿe) – und man kann mit ihm sehr gut, lange und vertieft über Autos reden. Was kann man von einem grossen Künstler mehr verlangen?

Max Küng (*1969) stammt aus Maisprach (BL), wo er auf einem Bauernhof aufwuchs. Seit zwanzig Jahren schreibt er Texte und Kolumnen für Das Magazin. Diverse Bücher und Romane, zuletzt erschien die Kolumnensammlung „Die Rettung der Dinge“ im Verlag Kein & Aber. Derzeit arbeitet er an seinem neuen Roman, der im Frühling 2021 erscheinen wird. Max Küng lebt in Zürich. Er ist verheiratet und Vater zweier Söhne. Er fährt gerne Velo.

- Werke von Francisco Sierra werden auch in ‘S-chanf 4+2’ ab dem 30. Juni in von Bartha, S-chanf (Engadin) zu sehen sein.

Untitled, 2019

Oil on canvas

61 x 46 cm

De Bloemenkops, 2015

Oil on canvas

220 x 170 cm